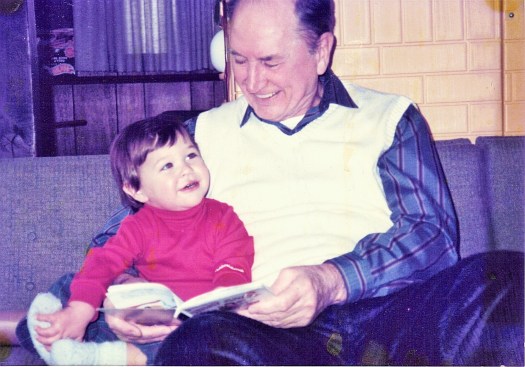

My dad with one of his grandsons

BY KATHY P. BEHAN

Today it’s tough being a dad. It’s not like the old days when a man was considered a good father simply because he brought home a good paycheck. Men can’t get off that easy anymore.

Fatherhood is no longer a spectator sport. Men are expected to participate in every aspect of their children’s lives. Along with changing their kids’ diapers, they’re changing their offsprings’ perceptions of what it means to be a man, and more specifically, a father. That’s why today’s dads usually have to forge their own path through the fatherhood jungle. They’re charting new territory because their own dads often took a simpler, less-demanding route.

There are some exceptions. My dad, for instance, was a “hands on” father long before it became fashionable. He showered my sisters and me with his good humor, love and attention. Sure, he helped with our “maintenance,” but he also had a deep interest in what we were all about. He talked to us about (almost) everything, and made sure we knew we could always come to him no matter what.

He had high standards too, encouraging us to pursue any educational or occupational dream that we had. This was fairly revolutionary since except for him, we were a household of females in the 1950s, and the feminist revolution had yet to take place. My dad probably knew the importance of encouragement because he didn’t get any from his childhood family. Despite this, he still managed not only to make it through college, but also through law school at night.

But that’s not what I find most remarkable. I’m most impressed that my dad was able to give us such unconditional love and support without having received these benefits himself in his youth. Despite a Dickensian childhood filled with poverty, the death of his mother, being placed in an orphanage, and adjusting to life in a foreign country, he was able to create, what one of my cousin’s dubbed a “Father Knows Best” family.

He was a great role model not only as a father, but also as a person. He taught us about social responsibility, and the importance of getting involved. Over the years, I’ve watched in admiration, awe and occasionally fear, as my father intervened in situations where others just stood in shocked immobility. He’s offered assistance and comfort in a wide range of situations, sometimes even putting himself in physical jeopardy in the process.

I’ve seen him break up fights, come to the aid of a child being physically abused by his mother, and help a man having an epileptic seizure. No, my dad’s not a policeman or a physician, he’s just a concerned, caring individual who thinks it’s everyone’s responsibility to help people in need.

There’s one incident that really stands out in my memory. While driving me home from a party, he told me to be on the lookout for a woman he had passed on the side of the road. We spotted her moments later plodding through the snow in high heels. My father pulled over and asked if she was all right. She burst into tears and the story tumbled out of how she had come to be wandering in the snow, late at night. “He just left me at the restaurant,” she tearfully explained, “and I didn’t have enough money for a cab.”

It seems her date deserted her because she wouldn’t consent to sleep with him. Getting back home was a problem not only because of her financial situation, but because she didn’t want to disturb her mother who was babysitting her young son. Without hesitation and despite her protests, my father delivered her safely to her door a full 40 minutes out of our way. That woman undoubtedly saw the seamy nature of man that night, but thanks to my father, she also saw the good side as well.

My dad isn’t perfect. He tends to categorize us, and has a hard time seeing us in a different light. For instance, I was the “party girl” who didn’t take school or anything else, for that matter, too seriously. This was certainly true when I was in high school, but I became much more responsible in college. However, my dad experienced a time lag in his appraisal of me. I think it was years later, maybe after the birth of my third child, when he realized I was no longer so flighty.

At times, he could also be pretty patronizing. Even though he taught us to think for ourselves, and encouraged us to pursue even a traditionally male occupation, he’d also say things like, “You’re too pretty to be upset.”

On the whole though, I think his track record is pretty remarkable. So on Father’s Day, my thoughts turn to my dad, and all the other men who have done their most important job well — being good fathers.

Like it or not, kids look up to their dads more than anyone else. They’re the true everyday heroes who have a unique place in our lives. We come to our fathers for so much more than just the proverbial allowance and car keys. Dads are the ones we run to first for fun, for approval and for help. No one makes us feel as safe, or as loved.

So Dad, even though there are lots of other people in my life, no one can ever take your place in my heart.

Happy Father’s Day!

Kathy P. Behan, a mother of three, is a nationally published freelance writer, specializing in health and family issues.

Uncle Mike

Uncle Mike

BY KATHY P. BEHAN

BY KATHY P. BEHAN By Kathy P. Behan

By Kathy P. Behan